Coronavirus Exposes the Hidden Risks of a Global Supply Chain

Henry Ross Perot was a billionaire, philanthropist, and politician but most of all, he was a businessman. He quit IBM in 1962 to found Electronic Data Systems which he later sold to General Motors. Later, he founded Perot Systems which was sold to Cisco in 2009.

He liked to call things as he saw them. He made it no secret that he was disillusioned by GM’s slow pace of innovation and decision making. In 1992 during a Presidential debate with Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush, he warned about the North American Free Trade Agreement, which had just been tentatively agreed to by Canada, the U.S. and Mexico.

“You implement that NAFTA, the Mexican trade agreement, where they pay people a dollar an hour, have no health care, no retirement, no pollution controls, and you’re going to hear a giant sucking sound of jobs being pulled out of this country.”

Perot could see the logical end this agreement would take. Instead of creating better trade and introducing American products to the Mexican and Canadian consumer, CEOs would use the agreement as a blunt instrument to bludgeon the big private sector labor unions into submission. After signing a series of terrible labor contracts, NAFTA would provide a means of escape for corporate managers who were lamenting how the deals they signed now made their products uncompetitive.

Following right behind Mexico, China lined up as another great source of “low-cost” components previously manufactured in the US.

A study published April 13, 2015 by The Economic Policy Institute, concluded that the U.S. lost about 850,000 jobs from 1993 to 2013 as a result of NAFTA and more than 5 million U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost between 1997 and 2014, and most of those job losses were due to growing trade deficits with countries that have negotiated trade and investment deals with the United States.

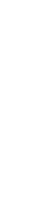

These jobs, which were once a pathway to middle-class income levels, as was the case for my parents, were now used to fund foreign governments who, as Perot said, paid people very low wages, provided no health care, no retirement, no worker safety regulations and no pollution control. Capital investment levels, a key driver of productivity and innovation, dropped as cheap foreign labor lessened the need for automation.

Unfortunately, buying materials and components from another country isn’t the same as buying them from a different county or state.

While regulations and standards may vary somewhat from state to state, the overall standards around the country are similar enough to allow for long range planning and lean-supply chain and capacity management. Not so when dealing with other countries.

Whether it is the impact of instability from constant movement of foreign governments from left to right and back again, or the lack of transparency we see from stable, but more authoritarian regimes such as China, trying to cost-optimize supply chains that stretch around the world is fraught with risk that is too often downplayed until it is too late.

This week we are seeing this play out with the ongoing coronavirus outbreak (see: What Apple, P&G, Walmart and other U.S. companies are saying about the coronavirus outbreak).

Those companies who produce locally to sell locally (think McDonalds, Domino’s Pizza and Starbucks), will take a hit to local revenue in affected areas, but won’t see their operations impacted in the US or anywhere not affected by the outbreak. But those who rely on the import of foreign made materials, components or finished products such as Apple, Walmart, clothing apparel and automotive manufacturers, are at risk of having domestic operations severely impacted as the supply pipelines dry up due to the shutdown of foreign manufacturing.

It’s not just manufactured items that are at risk.

A report last September by NBC news revealed that the vast majority of key ingredients for drugs that many Americans rely on are manufactured abroad, mostly in China. Imagine a national outbreak of a disease and being unable to supply the necessary treatments because the source of key ingredients was shut down due to the same disease.