What is Cash Flow Return on Investment?

When looking for good businesses to buy (even if we are only buying a small portion), we focus primarily on easy-to-understand fundamentals such as demonstrated consistent sales and earnings growth, along with favorable long-term economics and an attractive price.

While the first two criteria are easily measured, determining the last two can be highly subjective and downright frustrating.

This article will focus on one approach to identifying an attractive price.

Warren Buffett often refers to the idea of a business having a “moat” that will protect its “castle.” Another way of saying this is that we want to see some sort of long-term competitive advantage that will allow it to continue to earn high returns on its capital. In the following excerpt from his 2007 Shareholder’s Letter, Buffett expanded on this idea:

A truly great business must have an enduring “moat” that protects excellent returns on invested capital. The dynamics of capitalism guarantee that competitors will repeatedly assault any business “castle” that is earning high returns. Therefore, a formidable barrier such as a company’s being the low-cost producer (GEICO, Costco) or possessing a powerful world-wide brand (Coca-Cola, Gillette, American Express) is essential for sustained success. Business history is filled with “Roman Candles,” companies whose moats proved illusory and were soon crossed.

Porter Stansberry, a highly successful investment writer, has often referred to this as being “Capital Efficient:”

To beat the stock market over time, a company must be extremely capital-efficient (In other words, it must be able to grow without huge, ongoing capital expenditures.) And it must have a unique brand and product – a “moat” to protect it from competition.

Some of the names that Porter includes in this category are Apple, Disney and Hershey.

The final piece of the puzzle is then buying those good businesses at a favorable price. There are many ways to determine what price is favorable. In researching for this article, I looked at several valuation models used by prominent value investors. Harris Associates, which manages the Oakmark Funds, says that its goal is to pay two-thirds or less of the intrinsic value of the business.

Buffett is a little less precise, simply stating that he wants to buy at a discount to intrinsic value but is coy about what a sufficient discount may be. Most likely, it varies depending on the individual business.

In both cases however, these investors are focused on determining the intrinsic value of a business and then comparing that value on a per share basis with the current market price of the stock.

So, what exactly is intrinsic value? Buffett defines it like this:

Well, intrinsic value is the number that if you were all-knowing about the future and could predict all the cash that a business would give you between now and judgment day, discounted at the proper discount rate, that number is what the intrinsic value of a business is.

Now, when you look at a bond, such as a United States government bond, we can easily determine its intrinsic value because we know how much we are going to get back. It says it right on the bond. It says when you get the interest payments. It says when you get the principal. This makes it very easy to calculate the value of a bond at any point in time. It can change tomorrow if interest rates change, but the cash flows are printed on the bond and they do not change.

However, unlike bonds, cash flows aren’t printed on a stock certificate. So, we are required to find a way to look at these businesses in the way that we would look at a bond and say this is what we think it’s going to pay out in the future.

This is where Cash Flow Return on Investment (CFROI) can help us.

Outlined in the 1999 book by Bartley Madden, “CFROI Valuation: A Total System Approach to Valuing the Firm,” CFROI is a valuation metric that is based on the idea that, over the long-term, the stock market determines stock prices based on the net present value based on a company’s discounted expected cash-flows and not on its accounting earnings per share (EPS), or other measures of corporate performance.

For any company, CFROI is essentially the internal rate of return (IRR).

CFROI is compared to a hurdle rate of return, usually the cost of borrowing (interest rate required to issue a new bond) for the business.

To determine whether the business is increasing or decreasing in value, the CFROI must exceed the hurdle rate to satisfy an investor’s expected return.

Typically, when companies undertake specific business initiatives such as an acquisition or an expansion into a new business line, they prepare a “business case” that factors in the forecast amounts and timing of all cash outflows and inflows over the estimated project life. An internal rate of return can then be calculated, which is simply compared to the firm’s hurdle rate (their return on cash investments) to decide whether to proceed with the project.

As an example, let us assume that a mushroom farmer in southeastern Michigan wants to start selling at a major market on the west side of the state and needs a new vehicle to transport his product to the market.

The initial outflow of cash is the purchase price of $50,000. Once the truck starts making deliveries to the new market, the new sales will result in $10,000 of operating cash flow each year. After five years, we can sell the truck for $20,000 as it has reached the end of its useful life.

Example – Purchasing a New Delivery Truck

Purchase Price: -$50,000

Year 1 Cash Flow: +$10,000

Year 2 Cash Flow: +$10,000

Year 3 Cash flow: +$10,000

Year 4 Cash Flow: +$10,000

Year 5 Cash Flow: +$10,000, +$20,000

Based on these numbers, we can calculate that the return on investment for the new truck is just slightly more than 10%

We can expand on this premise, applying it not merely to a specific project like the example above, but to an entire company. Like the IRR calculation of any single business initiative, the CFROI metric is a proxy for the company’s total economic return.

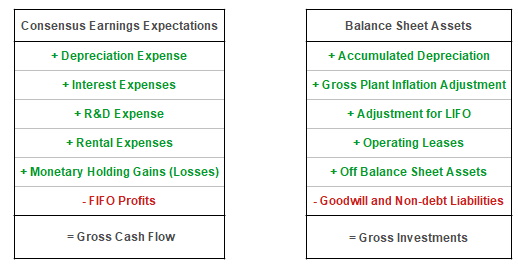

To do this, the methodology corrects subjectivity by converting income statement and balance sheet information into a CFROI return, a measure that more closely approximates a company’s underlying economics. The resulting returns are objectively based and can be viewed to assess the firm’s historical ability to create or destroy wealth over time.

To calculate CFROI, the financial information for a company is modified in order to make sure different methods of managing costs and assets are being accounted for. In this example, perhaps instead of purchasing the truck, the farmer struck a deal to lease the truck.

In this case, the truck would not be carried on the businesses balance sheet as if it were purchased and would, therefore, possibly distort the ROI calculation. In addition, other, non-cash entries on the balance sheet such as depreciation and goodwill are added or subtracted to create a metric called “gross investment” while net income is modified to reflect cash flows.

Consensus Earnings Expectations

GROSS CASH FLOW X GROSS INVESTMENT = RETURN ON GROSS INVESTMENT

The above information will then be used to calculate a company’s IRR (CFROI), from which then a “warranted value” for the stock can be determined.

This provides a consistent, holistic approach that can be used to compare operating performance across a portfolio, a market or a global universe of companies.

Doing this for every business is time consuming and requires lots of computing power, so you can imagine that a smaller firm like ours would be overwhelmed with such a task, and you would be correct.

We use a subscription service to obtain this information from a database of CFROI’s for over 18,000 companies worldwide. Historical records of up to 20 years are maintained for U.S. companies and up to 10 years for non-U.S. companies. As a “bonus” many REITs and Master Limited Partnerships are evaluated as well.

One last word about this concept. Just because we have found a great company and were able to buy it at a great price doesn’t mean that we should expect immediate success. In fact, very often we find these bargains amid a broader decline like in February and March and sometimes the sell-off continues after we have bought the stock. As value investor Howard Marks points out in his excellent book The Most Important Thing, “Being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.”

In the short-term, even the best investors are going to look wrong from time to time. If we’re not okay with that, then we should only invest in Treasury Bonds. But over the longer term, we believe that finding a good business, that’s attractively priced and that the market is starting to reward, provides us with a good opportunity to achieve our investment goals.